3.4 Stamping your language passport

What does it mean to be a global citizen when it comes to languages? How and why do individuals use different languages in different settings, and how can societies protect and promote linguistic diversity in times of globalisation? Unit 4 of the GCMC toolkit deals with these and other questions by connecting the dots between global citizenship, language and diversity and fostering a critical look at the traditional role of ‘language’ in global citizenship education.

A fine activity to make pupils familiar with multilingualism and language diversity is the language passport – activity 1, exercise 2 from the teaching module, adapted from the Steunpunt Diversiteit & Leren (Support Centre for Diversity & Learning) of Ghent University in Belgium. At Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning, located in the bilingual provincie of Fryslân in The Netherlands, we appreciated the way in which this exercise brings to the fore how multilingual virtually all of us are, even though we might not be very conscious about it.

Language and social setting

The exercise also elicits how people use different languages in different social settings. In Fryslân, this is an everyday experience for all speakers of Frisian: they may use the Frisian language at home or among friends, but they are very likely to switch to Dutch in more formal domains of society. They may usually speak Frisian, while at the same time hardly ever write it. While Frisian may be their mother tongue, they probably have the largest vocabulary in Dutch, especially when it comes to formal jargon.

These are familiar phenomena for everyone who knows a language or language variety that is not the dominant language of society. This applies to speakers of regional or indigenous minority languages, but also to people (and possibly next generations) who migrated abroad and speak the language of their former (or ancestral) homeland. The same goes for urban or rural vernaculars – non-standardised language varieties – that people feel comfortable speaking in certain settings, while switching to the standardised variety of this language in other, more public or formal settings.

Even people who think they really have only one language and nothing more, will find out when they come to think of it that they most likely will use at least some terms and phrases from other languages. Therefore, we believe the language passport exercise can be made suitable for schools in any linguistic context. In short, the language passport exercise shows how mulitlingual we are as individuals and what a wealth of linguistic diversity every group of students collectively brings to class. It is a richness that we encourage teachers to tap into in their practice.

All the languages you know

We ran the language passport exercise with a group of first year students of different ages, genders and linguistic backgrounds in a teacher training programme at NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences in Ljouwert/Leeuwarden, the capital of the Dutch province of Fryslân. NHL Stenden is the main institution in Fryslân for training teachers.

After explaining the rationale of the exercise, we encouraged the students to include in their language passports all the languages they know and occasionally use, emphasising they did not have to be fluent in this language at all. As long as they use words or phrases from this language even if only in one specific context, like in sports or gaming, or in a joking way with one particular friend, it is worth mentioning it. We also encouraged to add non-standardised language varieties, like urban or rural vernaculars. This way, we tried to convey the message that all language varieties are of equal value.

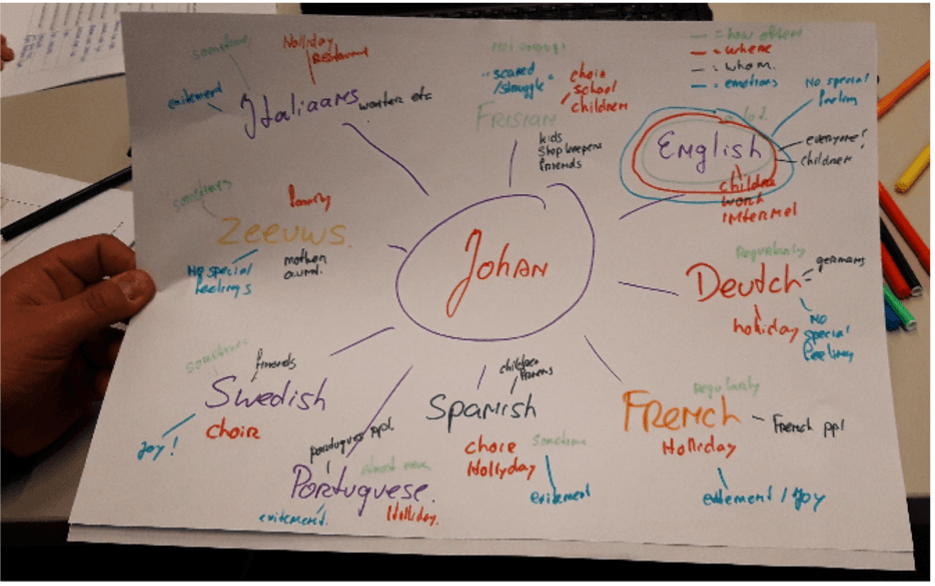

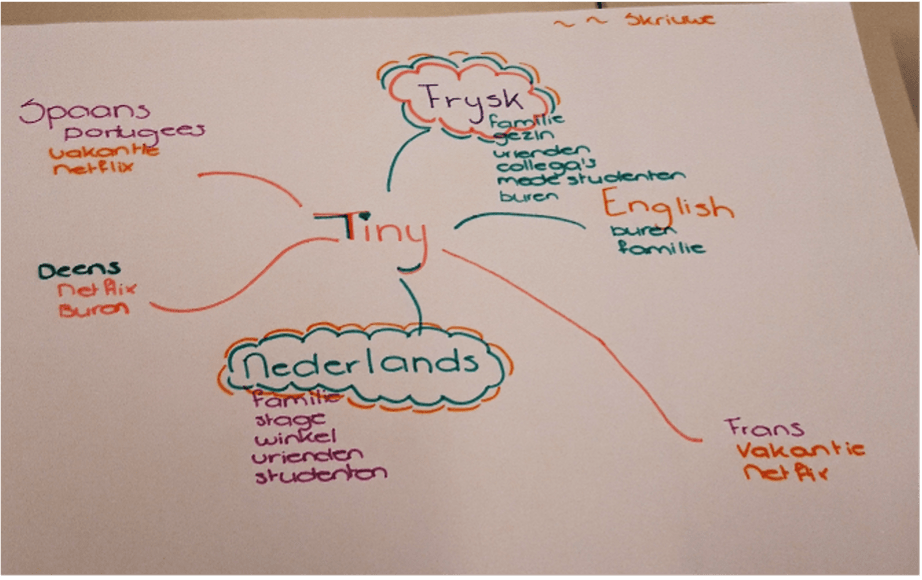

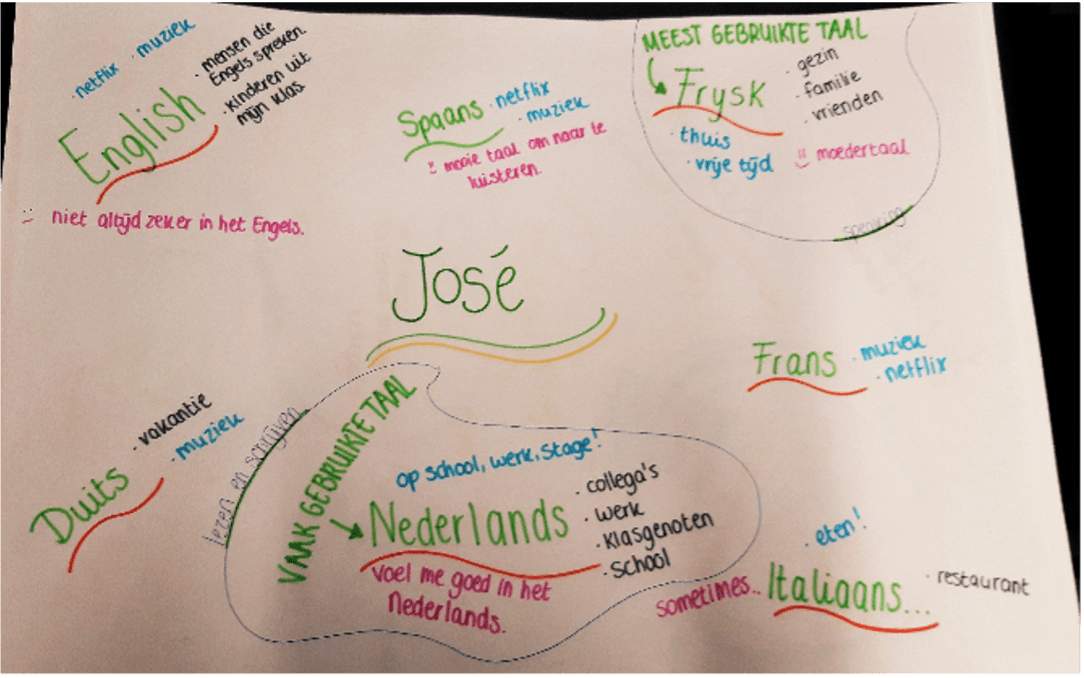

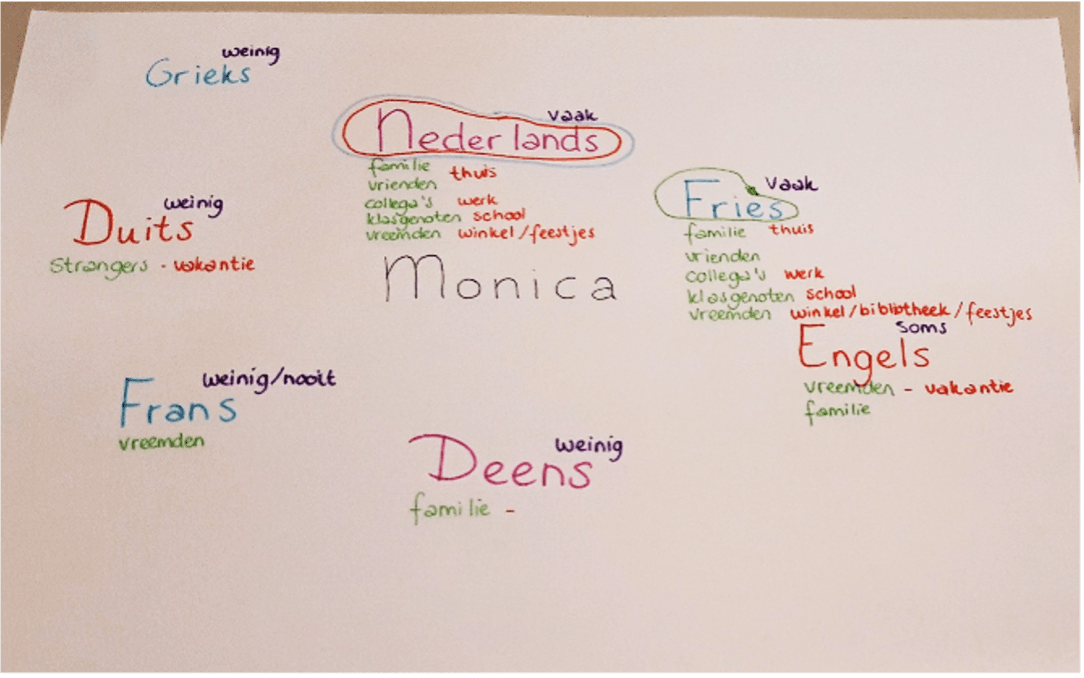

Each student was given an A3 piece of paper, wrote down their name in the middle and added their languages and dialects in a circle around their name (part B of exercise 2). For each language, they added information – in different colours – about whom they speak it to, in which situations they speak it, key feelings and emotions they attach to it, and how often they use it (2C). Students were then instructed to encircle the language they felt most proficient in for speaking, for reading, and for writing (2D).

Getting engaged

During this part of the exercise, it was striking to see how the students engaged with each other and expressed surprise about the number of languages they could think of that they at least occasionally use. On a question from one of the students, we decided it was alright to also include languages only ‘passively consumed’ by hearing it in for example Netflix series (even if for their understanding they were mostly relying on subtitles, in this case Dutch or English).

This section of the exercise also raised a discussion about what a language or language variety actually is. Could one include the urban dialect of their parents’ home town; is the vernacular of one’s rural home region really something worth mentioning? At this point, teachers can take the opportunity to refer back to debates touched upon elsewhere in the module, about issues of social prestige and politics determining whether a language variety is considered to be an official language or ‘just’ a dialect.

Subsequently (2E), students were asked to answer questions about which language they would use in twelve different situations. The students’ answers unveiled that English tended to be the dominant language in entertainment and more international aspects of our lives (holidays abroad, music, online games, searching internet, watching series and movies). Frisian-speaking students typically reserved their mother tongue to the spheres of home and friends, while swithcing to Dutch in more formal situations.

Depending on the pupils’ or students’ age and educational level, the exercise section mentioned above can be used as a starting point for a discussion (see 2F-H) about the social prestige of languages: the more a language is used in formal domains of society, the higher its social prestige. The language passport exercise helps to raise awareness about these status issues, which is the first step towards critically reflecting on one’s own biases and stereotypical thinking about certain languages and dialects: why do I subconsciously categorise someone speaking with a rural vernacular as being from a lower social background; to what extent do I feel that being a global citizen is connected to one’s proficiency in English?

As we consider ‘diversity’ to be a core tenet of global citizenship, we hope the language passport exercise will contribute to students’ appraisal of their own en everyone else’s multilingualism. Global citizenship as we see it is not about moving towards one globalised version of English, it is about being genuinely open and curious towards other cultures and languages and appreciating their diversity as a source of enrichment and joy.