Learning Objectives

- Gaining knowledge about global efforts to protect and promote linguistic diversity

Resources needed

- internet connection

Warning!

You can try out all activities and excercises, but you can't save any data. Please login or create a free account to save your data.

Exercise 1: Background knowledge on the protection of linguistic diversity

There are different ways to protect and promote languages. One approach includes measures that are initiated by governmental organisations or international institutions. Maybe in your country’s constitution language(s) is/are mentioned? Or perhaps there are explicit language laws?

Which conventions, laws or treaties do you know that protect languages or that relate to linguistic rights? List the documents you are familiar with and explain how they relate to languages.

Did you come up with many examples? Or did you find it difficult to think of any conventions, laws or treaties that address linguistic rights? Below you can find a selection of different international agreements, some of which you probably know, that point out language rights. Click on the buttons to find out more about how these agreements protect language rights.

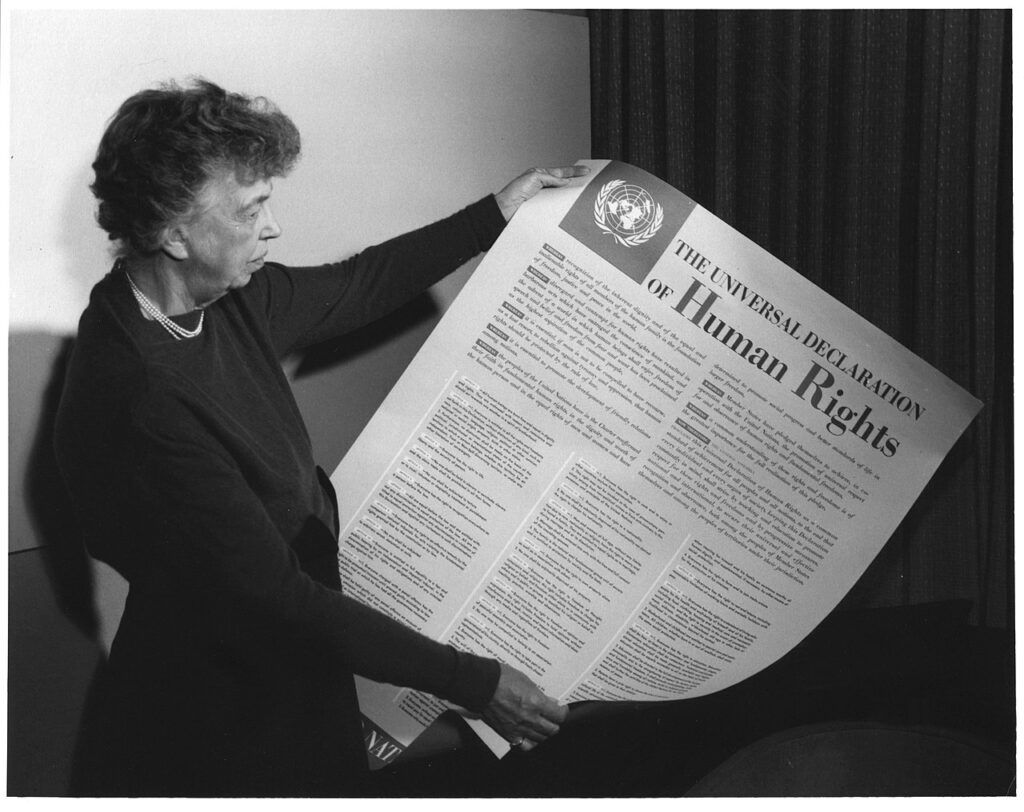

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations (the UDHR is not a treaty and has not been signed or ratified by states). The declaration was drafted by representatives from all regions of the world and for the first time, countries agreed on freedoms and rights that deserve universal protection. The UDHR was translated into over 500 languages. Article 2 explicitly states that no one must be excluded from the protection of their universal freedoms and rights based on their language. The UDHR constitutes the premise for International Covenants on Human Rights that followed, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

From 6–9 June 1996, the ‘World Conference on Linguistic Rights’ took place in Barcelona, Spain, during which “The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights” was adopted by associations, NGOs and institutions that attended the event. The document was drafted by a group from CIEMEN (a cultural, not-for-profit, non-governmental Catalan organisation), the Catalan PEN Club (PEN international is an NGO advocating for freedom of expression), and experts from around the world. The declaration sought to fill the gap of a missing common standard for linguistic rights; and promotes multilingual education, respect for linguistic diversity, and emphasised their role in strengthening tolerance and peace. The declaration is not formally adopted by UNESCO.

a) On 14 November 1960, during its meeting in Paris and at its eleventh session, the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, adopted the “UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education”. The Convention occupies the foremost place among UNESCO standard-setting instruments in the field of education. It is the first international instrument which covers the right to education extensively and has a binding force in international law. This Convention, which does not admit any reservation, has so far been ratified by 106 States. In article 5, the convention addresses the right of national minorities to carry out their own educational activities.

a) The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) was adopted in 1992 by the Council of Europe (CoE) and entered into force 1998. The Language Charter’s objective is to protect regional or minority languages as “expression of cultural wealth”. In the charter, regional or minority languages are defined as “traditionally used […] different from official language(s)”. The charter’s definition does not include dialects or migrant languages. The ECRML is monitored by the Committee of Experts on the ECRML. So far, the Language Charter has been ratified by 25 of the CoE’s member States.

a) The Council of Europe adopted the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) in 1994 and it went into force in 1998. The objectives of the framework convention are the protection of human rights, and to safeguard security and peace in Europe. The framework convention does not entail a definition for national minorities but contains the right to free self-identification (Art. 3) and the additional Explanatory Report describes applicable criteria. The framework convention is monitored by the Advisory Committee on the FCNM. The advisory committee also delivered a Thematic Commentary on Scope and Application [emded link: https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities/thematic-commentaries] (No. 4, 2016) of the FCNM. The FCNM has been ratified by 39 of its member states.

Exercise 2: Putting language rights into practice: Application of a framework convention

In exercise 1, you read about declarations, (framework) conventions, and treaties that relate to linguistic rights. In this exercise, you will learn more about the application of a convention, in this case the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) by the Council of Europe.

Here you can find the full text of the framework convention (in English).

TIP. The text is also available in other languages, e.g. French, German, Italian, and Russian.

You will be given a hypothetical case study and, subsequently, you will have to decide whether this situation is compatible with the FCNM.

In State X, persons belonging to the national minority B, constitute 25% of the population. Most of the B-pupils, visit primary and secondary education institutions with instruction mainly in the B-language. University entry exams and university education is provided only in the X-language.

Is this situation compatible with the FCNM? Focus on Section I and Section II of the FCNM. Please refer to the applicable article(s), explain why you chose the article(s) and why this situation is, or is not, in line with the FCNM.

It can be argued that the above-described scenario is not in line with the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, as it conflicts with articles 3.1, 5.2, 12.3, and 14,2 (articles can be found below). The situation creates a disadvantage for the B-minority. Excluding the B-language from tertiary education is an act of discrimination and poses a situation of unequal opportunities in terms of access to education. It forces the B-minority to assimilate into the X-majority, if they want to pursue a university degree. The language prerequisite to enter university also pressures parents and guardians to consider majority school education for their children instead of sending them to primary and secondary schools where the main medium of instruction is the B-language. Therefore, deciding to send children to schools with instruction mainly in the B-language can result in a disadvantage for pursuing tertiary education.

FCNM Article 3.1 “Every person belonging to a national minority shall have the right freely to choose to be treated or not to be treated as such and no disadvantage shall result from this choice or from the exercise of the rights which are connected to that choice”

FCNM Art. 5.2 forced into assimilation “Without prejudice to measures taken in pursuance of their general integration policy, the Parties shall refrain from policies or practices aimed at assimilation of persons belonging to national minorities against their will and shall protect these persons from any action aimed at such assimilation.”

FCNM Art. 12.3 “3 The Parties undertake to promote equal opportunities for access to education at all levels for persons belonging to national minorities.”

FCNM Art. 14.2 “In areas inhabited by persons belonging to national minorities traditionally or in substantial numbers, if there is sufficient demand, the Parties shall endeavour to ensure, as far as possible and within the framework of their education systems, that persons belonging to those minorities have adequate opportunities for being taught the minority language or for receiving instruction in this language.”

Please reflect on the following questions:

In the context of your country,

What kind of possibilities are there for language communities, to maintain their languages in educational settings?

For example: [The regional education ministry offers possibilities to maintain your home language, such as the “home language classes”. If the number of students of a language group is sufficient a teacher can be employed to give classes in that language. This service is for primary education and the lower secondary level. But this service might vary between the different federal states. Apart from that you can find private initiatives such as afternoon classes in the pupils’ home language to which the parents can send their children. (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany)]

How can you access services that ensure language maintenance and which obstacles are there to accessing them?

One obstacle can be the bureaucracy of organising “home language classes” since it depends on a certain student number, there might not be enough pupils to get the funding for a home language teacher. The above mentioned private initiatives are also depended on the on the number of speakers in the area. If there isn’t a sufficient number and parents wish for language classes in their home language, they might have to send their child to languages classes in a neighbouring town.

Exercise 3: Language diversity online

Measures or projects to protect and promote languages can be initiated by governmental organisations or international institutions, but they can also be initiated by members of the language community. The linguistic landscape in public spaces is not only shaped through legal regulations, but they are also heavily influenced by the people interacting in those spaces. An example of this are online spaces, which are transformed by the actions of their users. In a time where we spend more time than ever in online spaces, it is crucial to address and highlight the importance of language diversity and representation in this domain.

Please watch this video, in which Fox Nakai interviews Kristen Sinclair about her article “The twitch streamers fighting to keep minority languages alive—Entertainment meets activism”, to get an insight into minority language representation online.

TIP. The video offers a subtitle in English and you can also reduce the playback speed, if you like.

Afterwards, please answer the following questions:

What were your thoughts when you watched this video?

Possible answer: [This video introduced me to a topic I am relatively unfamiliar with, which is minority language issues. I thought it was quite interesting to learn that these languages are also used online on gaming platforms! It makes me curious about the languages my pupils are exposed to when they are active online.]

What are examples of how minority languages are used on Twitch?

There are bilingual streamers who use two languages when they stream, for example, by introducing a word of the week, or by dedicating one day to only one language or by switching between two languages.

Why does Kristen Sinclair think it is important for minority languages to be used on Twitch?

She argues that it is important for the maintenance of these, often endangered, languages to be used outside of the classroom and textbooks. Gaming, maybe it be playing yourself, watching or commenting is a relaxed and natural way of using a language. She also points out that language also carries other values such as cultural identity and history. In Kristen Sinclair’s opinion, the Basque streamer Iruñe summed it up quite well when she said “Nowadays, if you’re not on the internet, you don’t exist.”

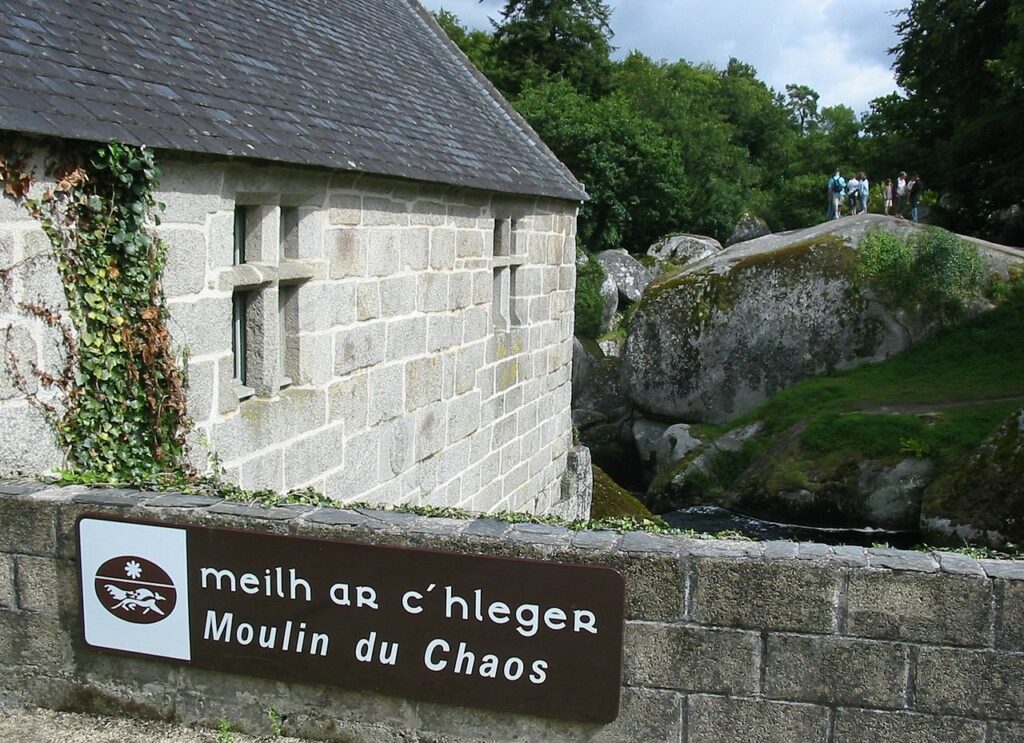

In the article “The twitch streamers fighting to keep minority languages alive—Entertainment meets activism” (Sinclair, 2021), someone who streams in Breton, a minority language in France, says:

What do you think about the streamer’s opinion that a “minority language needs to be everywhere the minority language speakers are”?

Possible answer: I think it is only logical that the language needs to be visible and actively used in all social domains. It should be possible for people to communicate, especially with their peers or other members of their community, in their language. It is great to see that different online communication channels, although there still some obstacles, can bring speakers of the same language together, as well as people who are interested in those languages. I think there are and will be many possibilities in the future to harness online spaces for a lively approach to language maintenance.

Please also reflect on the following questions:

According to you, what are the ways to value minority languages at school?

GCMC advice: Give them room in the class room, don’t punish pupils for using their minority language. If you work in a region where a minority language is spoken you can try to make that language visible in the school (posters for example).

Thinking of a school class that you teach, do you think it is important to your multilingual students to use their languages at school? If so, why/ why not?

Possible answer: I think it is very important for my students to use all their languages at school because it enables them to live out the different facets of their identity. It can have a positive effect especially in student-student interactions when they are not only allowed but also encouraged to make use of their other languages when working together. They can communicate freely and effectively.

TIP. If you are interested in reading the full article by Kristen Sinclair, you can find it online on The Verge’s website.